Persistent XSS in wordpress plugin rockhoist-badges v1.2.2.

Monthly Archives: March 2017

CVE-2016-10067

magick/memory.c in ImageMagick before 6.9.4-5 allows remote attackers to cause a denial of service (application crash) via vectors involving “too many exceptions,” which trigger a buffer overflow.

CVE-2016-10062

The ReadGROUP4Image function in coders/tiff.c in ImageMagick does not check the return value of the fwrite function, which allows remote attackers to cause a denial of service (application crash) via a crafted file.

CVE-2016-10063

Buffer overflow in coders/tiff.c in ImageMagick before 6.9.5-1 allows remote attackers to cause a denial of service (application crash) or have other unspecified impact via a crafted file, related to extend validity.

CVE-2016-10060

The ConcatenateImages function in MagickWand/magick-cli.c in ImageMagick before 7.0.1-10 does not check the return value of the fputc function, which allows remote attackers to cause a denial of service (application crash) via a crafted file.

CVE-2016-10064

Buffer overflow in coders/tiff.c in ImageMagick before 6.9.5-1 allows remote attackers to cause a denial of service (application crash) or have other unspecified impact via a crafted file.

CVE-2016-10069

coders/mat.c in ImageMagick before 6.9.4-5 allows remote attackers to cause a denial of service (application crash) via a mat file with an invalid number of frames.

CVE-2016-10068

The MSL interpreter in ImageMagick before 6.9.6-4 allows remote attackers to cause a denial of service (segmentation fault and application crash) via a crafted XML file.

CVE-2016-10071

coders/mat.c in ImageMagick before 6.9.4-0 allows remote attackers to cause a denial of service (out-of-bounds read and application crash) via a crafted mat file.

How Threat Modeling Helps Discover Security Vulnerabilities

Application threat modeling can be used as an approach to secure software development, as it is a nice preventative measure for dealing with security issues, and mitigates the time and effort required to deal with vulnerabilities that may arise later throughout the application’s production life cycle. Unfortunately, it seems security has no place in the development life cycle, however, while CVE bug tracking databases and hacking incident reports proves that it ought to be. Some of the factors that seem to have contributed as to why there’s a trend of insecure software development are:

a) Iron Triangle Constraint: the relationship between time, resources, and budget. From a management standpoint there’s an absolute need for the resources (people) to have appropriate skills to be able to implement the software business problem. Unfortunately, resources are not always available and are an expensive factor to consider. Additionally, the time required to produce quality software that solves the business problem is always an intensive challenge, not to mention that constraints in the budget seem to have always been a rigid requirement for any development team.

b) Security as an Afterthought: taking security for granted has an adverse effect on producing a successful piece of software. Software engineers and managers tend to focus on delivering the actual business requirements and closing the gap between when the business idea is born and when the software has actually hit the market. This creates a mindset that security does not add any business value and it can always be added on rather than built into the software.

c) Security vs Usability: another reason that seems to be a showstopper in a secure software delivery process is the idea that security makes the software usability more complex and less intuitive (e.g. security configuration is often too complicated to manage). It is absolutely true that the incorporation of security comes with a cost. Psychological Acceptability should be recognized as a factor, but not to the extent of ruling out security as part of a software development life cycle.

With a and b being the main factors for not adopting security into the Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC), development without bringing security in the early stages turns out to have disastrous consequences. Many vulnerabilities go undetected allowing hackers to penetrate the applications and cause damage and, in the end, harm the reputations of the companies using the software as well as those developing it.

What is Threat Modeling?

Threat modeling is a systematic approach for developing resilient software. It identifies the security objective of the software, threats to it, and vulnerabilities in the application being developed. It will also provide insight into an attacker’s perspective by looking into some of the entry and exit points that attackers are looking for in order to exploit the software.

Challenges

Although threat modeling appears to have proven useful for eliminating security vulnerabilities, it seems to have added a challenge to the overall process due to the gap between security engineers and software developers. Because security engineers are usually not involved in the design and development of the software, it often becomes a time consuming effort to embark on brainstorming sessions with other engineers to understand the specific behavior, and define all system components of the software specifically as the application gets complex.

Legacy Systems

While it is important to model threats to a software application in the project life cycle, it is particularly important to threat model legacy software because there’s a high chance that the software was originally developed without threat models and security in mind. This is a real challenge as legacy software tends to lack detailed documentation. This, specifically, is the case with open source projects where a lot of people contribute, adding notes and documents, but they may not be organized; consequently making threat modeling a difficult task.

Threat Modeling Crash Course

Threat modeling can be drilled down to three steps: characterizing the software, identifying assets and access points, and identifying threats.

Characterizing the Software

At the start of the process the system in question needs to be thoroughly understood. This includes reviewing the correlation of every single component as well as defining the usage scenarios and dependencies. This is a critical step to understanding the underlying architecture and implementation details of the system. The information from this process is used to produce a data flow diagram (DFD) which provides the best representation for identifying different security zones where data will be in transit or stored.

Depending on the type and complexity of the system, this phase may also be drilled down into more detailed diagrams that could be used to help understand the system better, and ultimately address a broader range of potential threats.

Identifying Assets and Access Points

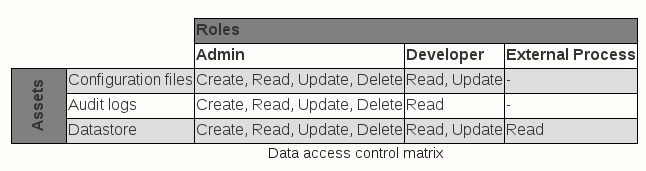

The next phase of the threat modeling exercise is where assets and access points of the system need to be clearly identified. System assets are the components that need to be protected against misuse by an attacker. Assets could be tangible such as configuration files, sensitive information, and processes or could potentially be an abstract concept like data consistency. Access points, also known as attack surfaces, are the path adversaries use to access the targeted endpoint. This could be an open port or protocol, file system read and write privileges, or authentication mechanism. Once the assets and access points are identified, a data access control matrix can be generated and the access level privilege for each entity can be defined.

Identifying Threats

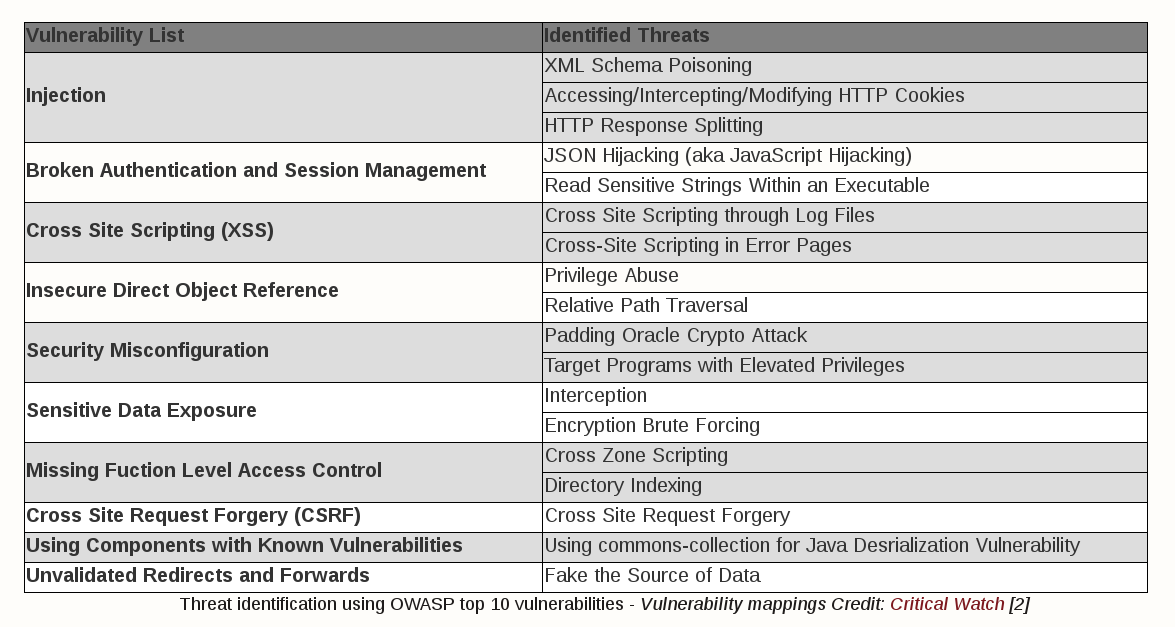

Given the first two phases are complete, specific threats to the system can be identified. Using one of the systematic approaches towards the threat identification process can help organize the effort. The primary approaches are: attack tree based approach, stochastic model based approaches, and categorized threat lists.

Attack trees have been used widely to identify threats, but categorized lists seem to be more comprehensive and easier to use. Some implementations are Microsoft’s STRIDE, OWASP’s Top 10 Vulnerabilities, and CWE/SANS’ Top 25 Most Dangerous Software Errors.

Although the stochastic based approach is outside the scope of this writing, additional information is available for download.

The key to generating successful and comprehensive threat lists against external attacks relies heavily on the accuracy of the system architecture model and the corresponding DFD that’s been created. These are the means to identify the behavior of the system for each component, and to determine whether a vulnerability exists as a result.

Risk Ranking

Calculating the risk of each relevant threat associated with the software is the next step in the process. There are a number of different ways to calculate this risk however OWASP has already documented a methodology which can be used for threat prioritization. The crux of this method is to determine the severity of the risk associated with each threat and come up with a weighting factor to address each identified threat, depending on the significance of the issue to the business. It is also important to understand that threat modeling has to be revisited occasionally to ensure it has not become outdated.

Mitigation and Control

Threats selected from previous steps now need to be mitigated. Security engineers should provide a series of countermeasures to ensure that all security aspects of the issues are addressed by developers during the development process. A critical point at this stage is to ensure that the security implementation cost does not exceed the expected risk. The mitigation scope has to be clearly defined to ensure that meaningful security efforts align with the organization’s security vision.

Threat Analysis/Verification

Threat analysis and verification focuses on the security delivery, after the code development and testing has started. This is a key step towards hardening the software against attacks and threats that were identified earlier. Usually a threat model owner is involved during the process to ensure relevant discussions are had on each remedy implementation and whether the priority of a specific threat can be re-evaluated.

How Threat Modeling Integrates into SDLC

Until now the identified threats to the system used to allow the engineering team to make better, informed decisions during the software development life cycle. Continuous integration and delivery being the key to agile development practices make any extra paper work a drag on the development flow. This also resurrects the blocking issues – Iron Triangle Constraint – mentioned earlier which might delay the release as a result. Therefore, it is essential to automate the overall threat modeling process into the continuous delivery pipeline, to ensure security is enforced during the early stages of product development.

Although there is no one-size-fits-all approach to automating threat modeling into SDLC, and any threat modeling automation technique has to address specific security integration problems, there are various automation implementations available, including Threat Modeling with Architectural Risk Patterns – AppSec USA 2016, Developer-Driven Threat Modeling, and Automated Threat Modeling through the Software Development Life-Cycle that could help integrating threat modeling into the software delivery process.

Should you use Thread Modeling anyway?

Threat modeling not only adds value to company’s product but also encourages a security posture for its products by providing a holistic security view of the system components. This is used as a security baseline where any development effort can have a clear vision of what needs to be done to ensure security requirements are met with the company benefiting in the long term.