The subject line is very irresistible. And the email came from a friend of mine, that only I hear from every 10 months or so whenever she is in town. So imagine my concern when I saw the following message:

Am so sorry that i didn’t inform you about my trip. I’m writing this with tears in my eyes. I came down here to Odessa Ukraine for a short vacation unfortunately i was mugged at the park of the hotel where i stayed. all cash, credit card and cell were stolen off me but luckily for me i still have my passports with me.

I ‘ve been to the embassy and the Police here but they’re not helping issues at all and my flight leaves in less than hours from now but having problems settling the hotel bills. the hotel manager won’t let us leave until i settle the bills, I’m freaked out at the moment.

I could hear my friend’s voice in the body of the email. She is also a world traveler with a deep interest in Central and Eastern Europe, and is definitely one to pop over to Odessa for a long weekend to see the famed Potemkin Steps or visit the city as part of a larger trek around The Black Sea. The poor punctuation and strange spacing confused me. Then again, she was panicked and under intense time pressure.

In other words, I was hooked. So I replied.

The email long tail finds the weak minds

Using various communications channels to finagle money or information from someone has a long and varied history. Many of the scams rely on the promise of easy returns. The Nigerian Prince is a case in point. The scam is similar to the 19th Century Spanish Prisoner scenario, but has usually relied mainly on mail, faxes, and email as part of a multistage setup that targets people with enough money to supposedly help smuggle millions of dollars out of an African country, often Nigeria (hence the name). Those that take the bait and pay the (fake) transfer fees are promised exponential returns on their investments that never emerge. There are scores of variations on the scam. For instance, a long-lost relative leaves a person a pile of money; to get the inheritance, the person needs to pay all the legal fees. But in general, most of these scams rely on greed to hook interest.

By contrast, “stranded friend” phishing attacks take advantage of a reader’s good will. We all want to help people we know and like. I certainly do. In my case, the conmen had used malware (probably a Trojan) to hack my friend’s email account and access her contacts. The message I received was addressed to around two dozen people. It’s unclear whether the hackers created their shortlist of targets using the communications history between my friend and her contacts or their geographic locations, but it seems likely given that other scams employ similar tactics. For example, hacked mailing lists from charitable organizations allow bad guys to set up fake charities and target the people most likely to donate based on past activity.

And email is cheap and easy. By stealing or buying stolen databases, scammers can obtain access to hundreds of thousands of addresses. With a bit of segmentation, they put the odds in their favor that someone will bite on their hooks.

Failed the friendship version of the Turing Test

In my case, my fake friend replied that I should wire several thousand dollars to a Western Union in Odessa. Before agreeing, I asked her to name a mutual acquaintance who had once joined us for dinner. Of course she could not. So I then called my friend’s fixed line (in another country) and left a voicemail alerting her that her email account may have been compromised.

Now I like to believe I’m smart enough to not fall for such scams. But criminals have access to the same analytics as governments and major corporations. They’ve also been practicing their trade for decades (sometimes centuries), so have tremendous insight into how best to influence even the strongest of minds. To stay sharp, there are several things you can do:

- Know what phishing is. Awareness is a huge step towards prevention. Knowing that the scammers are out there and masquerading as trusted contacts goes a long way to spotting them.

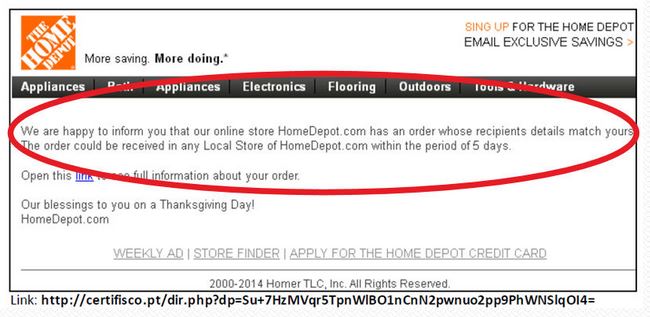

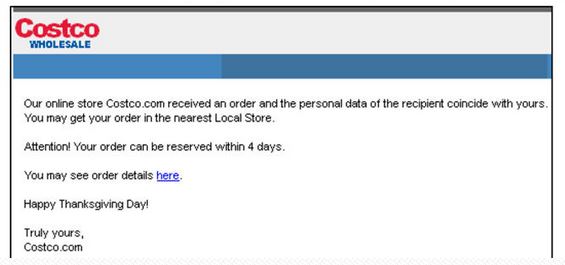

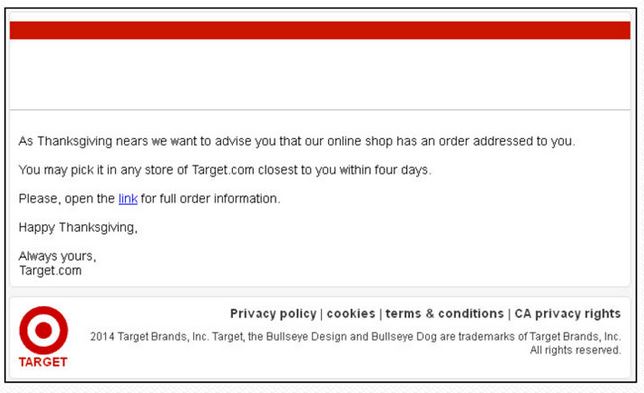

- Know what they’re after. Any email requests (or social media for that matter) asking for money should be immediately suspect. So too requests asking for personal data or account names and passwords.

- Watch for the signs. In addition to requests for money or hints that money may be needed, watch for poor spelling, bad grammar, and other oddities of speech. Check the email address itself – it may look like the supposed sender’s, but check for missing characters or additional characters added in. Pretty much all banks and most government and commercial organizations never ask for personal information, login information, or money via email; so if this information is part of the request, be very suspicious.

- Never click, copy, paste, or forward. For any email even remotely suspicious, do not click on anything, do not copy text and paste it into another email or document, and do not forward. To document the email (for alerting your friend or a company), the best approach is to take a screen shot.

- Don’t reply. Yes, I did, even though I saw the signs. But your reply tells the conmen that you pay attention to and open such emails. The bad guys will note this, and quite possibly save your email for another, more tempting scam later on.

The steps above may not be foolproof. But they can help ensure the adoption of a security mindset.

![]()

![]()